Bassinet image: The Wilmington Morning Star, January 10, 1918

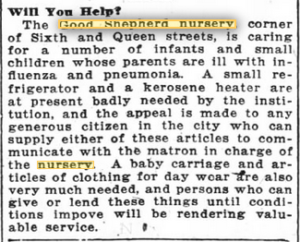

“Will you help?”

A picture showing tender nursery items was printed in a Wilmington paper in January, 1918, enticing moms to select the best for their babies. Only months later, in early October, The Wilmington Morning Star published an urgent appeal for blankets, undershirts, and flannel garments for babies whose parents were ill with influenza and pneumonia. Cribs were needed. Toys were needed. Volunteers to help cook for and feed children, and stay for night duty, were needed. There were more than a dozen children at the Good Shepherd nursery on the corner of 6th and Queen; their parents were hospitalized, sick with influenza and pneumonia.

The Wilmington Morning Star, October 5, 1918

In the paper the next day, Wilmingtonians read that there were forty-one children, “well babies are cared for there while parents are sick.” For three days in a row the paper published urgent requests for assistance. Well babies and those convalescing babies discharged from the hospital were under the care of Mrs. Henry J. MacMillan and Miss Meares. Both these women were Episcopal churchwomen.

Churchwomen have always responded “Yes!” From the earliest days of the formation of a diocese in North Carolina (1817), the church’s women have served the greater needs of the community and the world when the normal ways of doing so have seemed insurmountable. Beginning in the early 1800s, “working societies” built churches and paid clergy for parish congregations in their communities…and through the work of these churches, cared for the poor and hungry, the widowed and the orphaned. When wars came, these same societies took their skills and banded together in community women’s organizations to support their men by knitting, sewing, sending care packages and much-needed bandages and nursing care. It was true in the Civil War for both the Union and Confederate forces, the Spanish-American War, and in World War I.

The Spanish Influenza pandemic appeared in Wilmington by the end of September, 1918, and because of World War I, the city already had an organizational system in place to respond. In fact, New Hanover County had one of the first formally organized Red Cross chapters in North Carolina – the Wilmington chapter was organized in 1908. Histories note the establishment of a tuberculosis sanitorium started just before the war and efforts during the influenza epidemic. A Red Cross Wilmington Chapter history is filled with names of Episcopal men, women, and clergy (e.g., Mrs. Walter Parsley; the Archdeacon, the Rev. T. P. Noe; the Rev. Dr. W. H. Milton, rector of St. James; Mrs. J. V. Grainger; Miss Elizabeth Haile; W.H. and Walter P. Sprunt), especially in leadership positions, working side by side with women from every denomination and social situation.

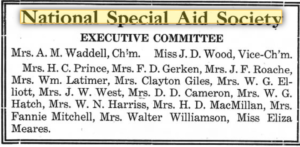

A sister organization, the National Special Aid Society, had a presence here as well. So, when the spread of the Influenza epidemic caused Dr. Charles W. Stiles, Assistant Surgeon General, Reserve, U.S. Public Health Service in North Carolina, to announce the closure of the churches, all worship services and activities theoretically were stopped. There was, however, a greater need at this point for Christian response, this time at home. The women in Wilmington did so by simply shifting their energies from support of the troops to support at home.

The Wilmington Morning Star, November 30, 1918

A number of women in the Special Aid Society were Episcopalians…and experienced in leadership as well as the necessary skills of knitting, cooking, and nursing. A number of the Executive Council women attended Episcopal churches. An announcement in the October 24 edition of the Morning Star gave a “send off” to Miss Elizabeth Haile, president of the St. Anne’s Guild at St. John’s Church “performing the duties of this office as well as doing other church and civic work.” She was “prominently connected with the Red Cross society…and when the emergency ward was established at the James Walker hospital to care for influenza and pneumonia patients, she was placed in charge.” When the crisis at home was over, she left Wilmington for New York to report to overseas nursing duty with the Red. Cross, according to the Wilmington history of the North Carolina Red Cross.

It was not only the church societies who united across denominations in patriotic support of first the war effort and then responded to the Influenza pandemic. Leadership came from Wilmington’s strongly patriotic women. Not unlike many women across the South, characteristically they represented families who had for generations held membership in organizations like the Colonial Dames, Daughters of the Revolution, and the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The chairman of the Special Aid Society was Gabrielle DeRosset Waddell, wife of Alfred Moore Waddell. Moore was well-known for his white supremacist politics and his leadership role in the Coup of 1898, becoming Mayor of Wilmington immediately afterwards. It’s a difficult challenge to understand the depth of faith and commitment to living a Christian life of serving others that this woman had and the face of racism that manifested itself in the anger and fear of the political life they lived. And yes, there were “colored” chapters of the Red Cross and Special Aid Society but records apparently may not have been kept.

Courtesy of Hake’s Auction website

The immediate needs of Wilmington’s children were announced on October fifth as the Good Shepherd nursery, financed by Patriotic Penny work, first appeared in print. As a pledge to the WWI effort, citizens contributed a penny a week and earned the right to wear the Patriotic Penny badge. The Fund was supervised and distributed by the Special Aid Society. Pennies were valuable. They were also easily collected in bottles placed around town in strategic public places and they added up. It was a simple matter in Wilmington to redirect the funds to Influenza epidemic support “to bear the entire cost of maintaining the Patriotic Penny nursery, established by the society at the corner of Sixth and Queen streets,” according to the Morning Star on October tenth. Babies would be cared for “indefinitely” until they could return home; those orphaned “being taken in the institution.” (Might this have meant the St. James Home?). The Special Aid Society assumed guardianship for every child and any and all expenses, depending on public contributions since regular weekly collections were so impacted by the epidemic.

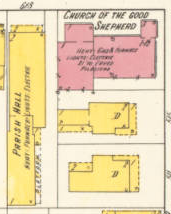

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1915.

A note of explanation is due here. Some history of the Church of the Good Shepherd, according to their historian, Peter Perschbacher, says that the parish hall was used as a “hospital” in 1918, which confirms the short-lived time period and special nature, and mission, of the nursery. Travis Souther, the Librarian for the North Carolina Room at the New Hanover County Library downtown found an article in the Bill Reaves files, dated 24 April 1966, stating “During the influenza epidemic of 1918 the building was used as a hospital through the interest of the Rev Frank D. Dean, then rector…In 1942, Miss Florence Huband began a nursery school which for 16 provided care for pre-school children.” Again, this seems to indicate that it appeared during the Influenza Pandemic and was not already a church nursery, and did not continue as one. It seems clear from the Sanborn map that the hall would have been more useful for this purpose than the church, especially since there were services, although rare, in the church. In the Morning Star, it was only called the “Good Shepherd nursery” in one of the newspaper articles before it was referred to in all future articles as the “Patriotic Penny nursery” and claimed by the Special Aid Society as being initiated by them at 6th and Orange streets, location of the Church of the Good Shepherd.

The Society’s efforts were significant and successful. By October 24th, the Morning Star reported the ladies’ work was being returned to troop support, and their Special Aid meeting and work room was being scrubbed “as clean as a hospital ward” as precaution against the “few new cases” of Influenza. “We take no risks because we know what it means to fight for the city’s restoration to normal.” Next day’s edition of the paper headlined an article “Patriotic Nursery Closed.” All babies with the exception of one had left and the nursery was issuing a call to persons who had loaned items to the nursery to retrieve them. More than sixty babies and small children had been cared for; all orphans had been placed with relatives or adopted. The last child would stay with one of the caregivers, either Mrs. MacMillan or Miss Meares – neither was identified by name.