St. Paul’s “Little Brick Church” (1914-1939), 16th and Market streets, Wilmington, N.C.

Enforced closures, open doors, and divine service

The St. Paul’s Vestry records, dated October 1918, didn’t mention the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918. It seemed to be just business as usual. A special called meeting on October 8th, noted the passing of vestryman and parish treasurer, John Victor Grainger, Jr., not mentioning the reason for his death. (We learned in Part 1 that Mrs. J. V. Grainger was very active as a volunteer for the Red Cross for war-time and influenza relief.) September’s minutes did include mention of his resignation. Later diocesan records and newspaper clippings show that he died of Influenza related pneumonia. A private funeral was held for him at his home on October tenth; the Rev. D. E. Gwathmey conducted it assisted by the rector of St. James, the Rev. W. H. Milton.

It seems the parish tried to maintain what normalcy they could, despite the closure of churches. At St. Paul’s regular meeting in October, business items were to accept the resignation of Thomas W. Davis, Esq. who had become a Major in the Judge Advocate General’s Department of the Army. The second was a resolution with regard to the death of John Victor Grainger, Jr. Rather than try to fill the positions emergently, the vestry chose to fill them at the congregational meeting in December. Finally, the rector would receive two loads of wood. Vestry records stop with this meeting.

Young Victor Grainger’s funeral service conducted at home was not unusual in Wilmington. Most deaths and funerals reported in the Wilmington Morning Star that month took place in residence, at the gravesite, in “open air,” or in the chapel at Oakdale and were officated by the various ministers and pastors of the local parishes. There were exceptions, however. The Rev. Milton conducted at least one funeral at St. James Church.

The Wilmington Morning Star, October 6, 1918

After carrying a story on September 14th that Spanish Influenza was breaking out in communities across North Carolina and that weather conditions had no effect, the Morning Star reported the news two weeks later that churches were to be closed according to the recommendation of the Board of Health. Pastors were “freely co-operating.” Worship and meditation at home were recommended at “the usual hours of services.”

The October 9th edition of the newspaper carried a lengthy story about a meeting with Dr. Charles W. Stiles, an Assistant Surgeon General, Reserve, U.S. Public Health Service in North Carolina, and a gathering of local clergymen and laity at which he updated them on the progression of the pandemic and what precautions to take. He had requested 30 physicians and 100 nurses from United States health service to help in North Carolina. Constantly casting a shadow over all this, there was concern that the epidemic was decreasing the wartime efficiency of New Hanover county – the shipyards were being crippled and the military camps were affected. As a result, cities with shipyards were receiving priority attention above agricultural rural communities.

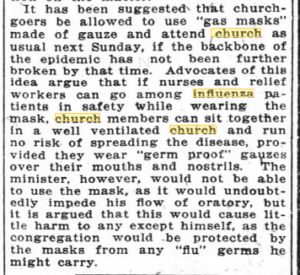

It was for this reason that precautionary measures were so important. Dr. Stiles considered the clergy as the obvious choice as community leaders who could “mold public opinion” and one of the best communication vehicles at his disposal. His update was accompanied by education. The Board of Health requested no funerals at church or in residences, only in open air and at gravesites, which people had been ignoring by continuing church funerals. To prevent what he called “spit swapping, to use the vernacular of the street” he encouraged learning the safe way to cough and sneeze, and not to do so directly in front. “Cover the mouth and nose” by handkerchief or hand, was the essential message to persons in crowded areas. He went on to suggest what we call today “sheltering in place” and “social distancing” and added that people should stop drinking whiskey and stop kissing! The counterpoint to all of this was the war effort, so much so that Stiles also discouraged dock and shipyard laborers from leaving their jobs. He urged them to remain at their patriotic duties until or unless they showed symptoms of the virus. No Episcopal clergy were named as having attended his meeting.

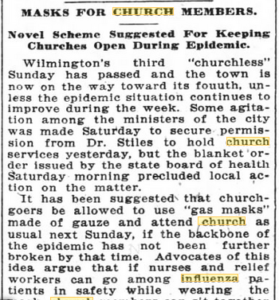

While health officials fought to keep public places closed, churches decided whether to comply or not with having church services and funerals and searched for alternatives that would allow church participation.

The Wilmington Morning Star, October 14 and October 20, 1918

What was surprising to find was that St. James agreed with the decision about the mandate for closed churches but provided an option. A letter from the rector, Dr. Milton, published September 29th, informed his congregation:

In as much as the board of health has ordered the churches of the city closed tomorrow for all services, I would urge upon the congregation of St. James church that they meet together as families at the usual hour of worship, morning and evening, and join in prayer or at least the prayers provided in the Prayer Book for family worship.

Remembering, especially to offer intercession for the sick and neglected, the physicians and the nurses of this community in the present crisis. Not forgetting those who in the service of their county, are facing the perils of war.

With earnest prayer that this crisis may pass speedily and that next Lord’s day may find us all once more in the Lord’s House. The church doors will be open as usual for private prayer and the bell will ring at 11 and 6 o’clock.

The Morning Star carried an expanded announcement from St. James a couple weeks later – that the church “Will be Open Today for Private Prayer – Bells at 11 and 6.” The church was ringing the bells at morning and evening hours as a call for family worship. It added:

The church doors will be open at all times between 3 and 6 for rest and prayer. In these days of enforced closing for public gatherings, opportunity is therefore offered the people to resort to the church for private mediation and intercession. “In the midst of life, we are in death: of whom then shall we seek for soccor, but of Thee, O Lord, who for our sins are justly displeased.” “They that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run and not be weary; and they shall walk, not faint.”

One of the Weekly Reports of the Special Aid Society commented that a woman decided to do her “divine service on Sunday even if there was no church. She held a worship service of her own and took up 45c, which she brought to our patriotic penny collection. Some colored people brought in one dollar in pennies and said that after this they meant to keep it up.”

Around the Diocese of East Carolina

The Journal of the Annual Council [Convention] of the Diocese of East Carolina (1919) had little to say about the closure of the churches during the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918. The Bishop, the Rt. Rev. Thomas C. Darst, indicated in his address to clergy and laity that in his diary for 1918, his last parish visits were October sixth. After that, he wrote: “Owing to the closing of the Churches, by order of local and state authorities, on account of the Influenza Epidemic, my appointments for the remainder of the month were necessarily cancelled.”

The report to the Council from the Trustees of St. Mary’s School in Raleigh, which was supported by the Diocese of East Carolina, had an interesting comment:

“it must be said, however, that not only the general prevalence of the epidemic of Influenza during the past fall and winter made such work all but impossible, but also that Mr. Osborne himself was for months totally disabled by a severe attack of that disease, so that for a time his friends feared a fatal termination of his illness. … The same unfavorable conditions have affected the internal life and administration of the School. The Influenza in Raleigh first became epidemic in St. Mary’s, and within a week of the opening in September, 1918, had almost broken up the routine of the work. The school had opened with the largest attendance in its history, with the exception of one year. In spite of the terrible epidemic it has maintained a very high average attendance, and a total enrollment during the year of 202 boarding pupils.

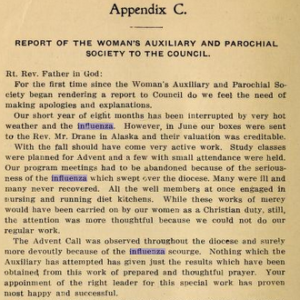

The Woman’s Auxiliary and Parochial Society to the Council (now Episcopal Church Women) Report had more. Describing their work over the past year, they noted that Influenza had been the cause of meetings being cancelled; the national Woman’s Auxiliary’s “Advent Call for Prayer” plans for the diocese been disrupted; and then proudly announced “Many members volunteered for service” during the epidemic. The Juniors were highly praised for their service, provided “with no suggestion from their secretary.”

Journal of Convention, Diocese of East Carolina, 1919. Woman’s Auxiliary Report

Many of the church women in Wilmington who were members of the Woman’s Auxiliary were members of the National Special Aid Society and Red Cross. They, along with women of other denominations whose normal church activities were curtailed by wartime efforts, had redirected their energies to meet the needs of their community during the pandemic.

As the spread of Influenza from the soldier populations in training locations and those returning home moved deeply into North Carolina’s communities, a new attitude was called for to deal with the pandemic it created. A Brief History of the Episcopal Churchwomen of the Diocese of East Carolina by Louise Bashford Hunt (a St. Paul’s parishioner!) described the epidemic as hitting East Carolina “with such force that convocation meetings were called off, and all work was carried on by correspondence.” For women in all dioceses in North Carolina, the “Advent Call” was a Call for United Prayer. The Woman’s Auxiliary in the Diocese of North Carolina reported to Annual Convention in 1918 that it was a call for response:

by all women of our Church for winning the war and for the days of Reconstruction,…Although the epidemic of Influenza prevented the carrying out of this plan fully in some places, in others it was a rare experience for our women, drawing them closer together in the study of the meaning of Prayer and of the spiritual needs of our own country and of the whole world. Through this experience, in the midst of war and pestilence…”

Sources:

1918 editions of The Wilmington Morning Star https://www.newspapers.com/

St. Paul’s Parish Records and Vestry Records, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church Archives, Wilmington, N.C.

Hunt, Louise Bashford. A Brief History of the Episcopal Church Women of the Diocese of East Carolina 1888-1988.

1918, 1919. Journal of the Annual Council, Diocese of East Carolina

https://archive.org/details/journalofannualc07epis/page/n5/mode/2up

1919, Journal of Convention, Diocese on North Carolina, Woman’s Auxiliary Report

https://archive.org/details/journalofannualc103epis/page/32/mode/2up/search/advent+call

New Hanover Red Cross History, “History of the Wilmington, N.C. Chapter American National Red Cross” https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p15012coll10/id/7173/rec/1

Ellen C Weig archivist@spechurch.com 2020.3.30