According to pandemic medical history review articles, among the things we know today about the Spanish Influenza pandemic is that there were clearly challenges. In 1918, recognition of the spread of the disease was not consistently understood by the public or embraced because of World War I homeland support efforts. That seems to be born out in many of the local Wilmington, North Carolina newspaper articles that mentioned influenza or pneumonia as the causes of hospitalization and death without understanding, in this case, the relationship of one to the other, at the same time with recommendations for dock and shipyard workers to remain on the job until they had active signs of illness. Another fact was the scarcity of medications, hospital beds, physicians and nurses, and treatments for related medical issues. A third was that public health information about prevention and precautions was varied tremendously depending on local health departments and outbreak severity. There were attempts to limit contact knowing that it was an airborne contagion and cautions to cover coughs and sneezes. Open air gatherings, hand-washing, and avoidance, including the use of masks, were recommended. Man¬agement of the medical issues was evolving; new developments included the idea of sterilization and antiseptic conditions introduced only recently. Antibiotics and vaccines available now were not back then. Additionally, there was no national unified message or communication, only reports shared in local newspapers, journals, and personal letters that updated the public, generally after the fact. And lastly, transportation advances in road building and railroads had opened up the country in ways that permitted the progression of Influenza out of communities where infectious diseases once would last only weeks. The movement of military forces for training and deployment exacerbated the spread of the Influenza. For individuals, however, medical folklore played a significant part: “bad air” meant keeping windows open, while staying warm was critical so you didn’t “catch cold.” It was in this setting that the Church had to react and respond to a rapidly expanding medical crisis.

Much of the work of the Church in 1918 was focused on support and care for the emotional and spiritual health of soldiers fighting in WWI and their loved ones at home working in wartime industry and shipbuilding. Prayer would become to virus what soldier, shot, and shell was to Germany’s troops. The work of the Church across the country, from hospitals, military notices and information, war-time chaplains, regional news, and many lengthy articles by clergy, as well as news from England and clergy there, filled the pages of the National Journal of the Protestant Episcopal Church, weekly. All the following clippings were taken from The Churchman, July 6 – December 28, 1918.

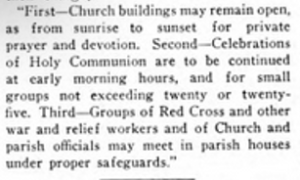

One news story in particular expressed the anxiety and dread of the Episcopal Churches in Philadelphia. On Thursday evening, October 5th the Board of Health announced the closure of schools and churches. The next day “the police brought formal notice of this action.” Influenza was spreading throughout the city. Bishop Rhinelander’s response was to ask for volunteer clergy to fill in for those who were ill. Furthermore, he emphasized the opportunity for prayer by people at home, urging them to gather between ten and eleven o’clock on Sunday to pray: 1st) for protection of American forces and for victory; 2nd) for united patriotism and loyal support of the Fourth Liberty Loan; 3rd) for relief from the danger of the epidemic, healing, and prevention of its spread. But while the Bishop urged support, some clergy protested the order. The Rev. Samuel Upjohn, of St. Luke’s Germantown, said, “The psychological effect of a decree of utterly closed shrines of God is far more likely to have fatal effect upon the stricken and upon those who labor under the apprehension of being sticken.” After meeting with Director Krusen of the Health Board, the bishop “obtained special permission for his clergy.” He agreed that it was the church’s duty to cooperate, but “it is evident that a too rigid enforcement of the order will tend to defeat its primary objective. The normal life and activity of the Church, if allowed to continue under careful restrictions, will work hand in hand with the public authority in saving and protecting life, and will also greatly tend to reassure and strengthen our people by disarming anxiety and panic which, as is well known, predispose to the infection of the disease.” At this point, he told his clergy the buildings could remain open, gatherings had to be small, and war relief workers and the Red Cross could use parish houses to meet. A later article describes the uncertainties of when to re-open.

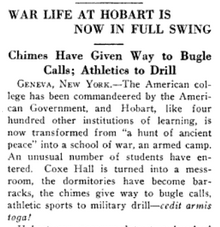

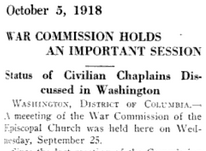

Here are some other examples published October 5th.

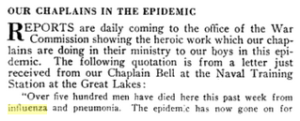

The next issue, October 12th, posted this article (excerpted) from the office of the War Commission quoting a letter from Chaplain Bell at the Naval Training Station at the Great Lakes. This is one of the first direct references to Influenza.

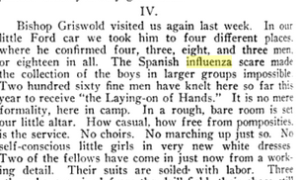

When Chaplain Bernard Iddings Bell penned his “Impressions” while at Great Lakes, one part of his message describes the visit of Bishop Griswold to the soldiers and how the Spanish Influenza made “the collection of the boys in larger groups impossible” for confirmation. As much as possible, Church tried to maintain normalcy – except in attire!

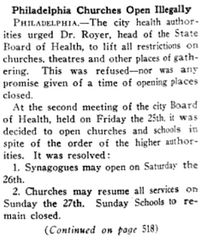

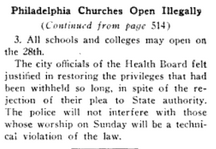

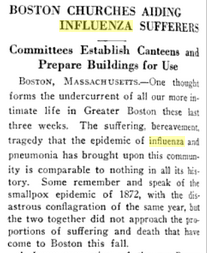

Reading more through October, there is an increasing presence of the Influenza epidemic filling in the spaces between war related news. For the next few weeks regional news stories mentioned cooking and feeding ministries and soup kitchens, churches staying open illegally, hospital ministries and direct spiritual care to the sick. Despite the original mandated closure of churches, the participation of the clergy and the response of the parishes as they grieved together and worked together to provide support within their communities. Influenza appeared, as Bishop Rhinelander had hoped, to bring people of the church into a united effort of prayer by action – through feeding ministries and nursing and medical care.

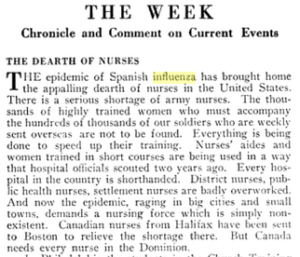

When a lack of trained nurses threatened care for American soldiers, an appeal for help in the October 19th issue was made. The young women studying at the Church Training and Deaconess House in Philadelphia gave up their studies and volunteered for emergency nursing. But more was needed.

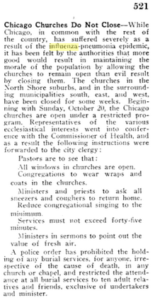

Here are a few more samples of items published in The Churchman. The Church was standing its ground, keeping churches open for prayer, working closely with the Red Cross on personal levels, and caring for those who were sick and the ones who cared for them in the most forceful way they could. Note the recommendations from Chicago for open windows,etc.!

When the closing of the Churches in Washington was protested, spiritual support was at the heart of the message. “No one will deny that to close the Government departments would be out of the question, except in the last resort, not-with¬standing the fact that they are veritable hotbeds of influenza. But it is just as contrary to public policy to close the churches and thereby weaken the spiritual power of the country. Spiritual force is even more necessary for victory than shot and shell and ships and cannon and aeroplanes.”

Sources:

The Churchman, Vol. 118. July 6, 1918 – December 28, 1918

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112073545888&view=1up&seq=9

(Saunders-Hastings, Patrick R. and Krewski, Daniel. “Reviewing the History of Pandemic Influenza: Understanding Patterns of Emergence and Transmission.” In Pathogens. 2016 Dec: 5(4): 66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti¬cles/PMC5198166/

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918. “The Public Health Response” https://virus.stanford.edu/uda/fluresponse.html

Ellen C Weig, archivist@spechurch.com

2020.2.30